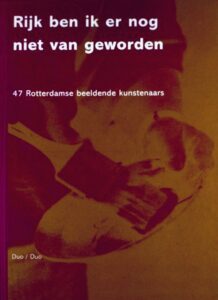

This is the title of a book published in 1997 by the Academy of Fine Arts, the Center for Visual Arts, and the DuoDuo Publishing Foundation in Rotterdam.

This is the title of a book published in 1997 by the Academy of Fine Arts, the Center for Visual Arts, and the DuoDuo Publishing Foundation in Rotterdam.

The reason for this book was the research conducted in 1994 on the history of Fine Arts in Rotterdam. To get an impression of the training of artists and their further development, interviews were conducted with 46 students (studying at the academy between the years 1945/1955).

The vast majority of the interviewees were born before 1934, and at the time of the interview, they were around 65 years old.

Now

I was reminded of this book when I read an article in De Volkskrant (dated March 28, 2024) about the gender pay gap in the visual arts. It turned out that female visual artists in the Netherlands earn on average 20% less than their male counterparts. This emerged from a new study by the Boekman Foundation, a knowledge center for arts and cultural policy. For the research, artists, museums, and gallery owners were interviewed, and data from the Central Bureau of Statistics was analyzed. I assumed that the income of visual artists would have improved since 1997, but I was mistaken.

According to the Boekman Foundation’s research, female visual artists had an average gross annual income of €16,900 between 2017 and 2021, while male visual artists earned €20,200. These average incomes also included additional earnings alongside their artistic practice. The incomes of both female and male visual artists are significantly lower than the statutory minimum wage (2024), which is €24,800 for full-time work. Fifty percent of visual artists with one or more jobs have a (personal primary) income of less than €2,000 per year.

Art scene (in Rotterdam) back then

From the 47 interviews, the following picture emerged: in the 1950s, the art scene in Rotterdam was in a gloomy state. In the post-war situation (after World War II 1940-45), the city was busy with reconstruction. There were few facilities, and even Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen did little to nothing for modern art/artists. At that time, artists were seen as people who did not do sensible things and only cost money.

Rotterdam ignored its artists. Looking back, it was a fatality for many Rotterdam artists to have worked in Rotterdam. In Amsterdam, they would have advanced much earlier because unlike Rotterdam, Amsterdam had a lively art scene. Rotterdam artists who did become successful include Klaas Gubbels and Co Westerik

Rotterdam ignored its artists. Looking back, it was a fatality for many Rotterdam artists to have worked in Rotterdam. In Amsterdam, they would have advanced much earlier because unlike Rotterdam, Amsterdam had a lively art scene. Rotterdam artists who did become successful include Klaas Gubbels and Co Westerik

The Academy of Fine Arts in Rotterdam built on the old concept of the Art Industry School, with the teaching staff consisting of craftsmen. The education was imperfect and poor. Modern trends were overlooked and denied. After the Cobra exhibition of 1948, there was a shift within the Academy, although art was mainly focused on production rather than experimentation. There was even an expression: ‘if you studied at the Rotterdam Academy, you are self-taught!’

There were hardly any girls at the Academy (of the interviewees, there were 36 male and 9 female artists). Students were not provided with tools on how they could survive (financially) in their profession. People were trained but in a field that offered a bleak future perspective. From 1949 to 1987, the BKR (Beeldende Kunstenaars Regeling) was therefore introduced, a scheme that provided artists with a (temporary) income in exchange for an artistic contribution. This allowed various artists, including those who later gained fame, to continue dedicating themselves to their work and further develop. Almost 6000 artists used it at some point. The scheme ended after 38 years.

Female visual artists in the Netherlands today, labor market position, career trajectory, representation

Here you can find the complete reasearch of the Boekman Foundation.

I have studied the report from beginning to end and summarized it for myself. Why did I do this? Art, in my opinion, is often highly romanticized and made into something exclusive. Attention is given to the ‘big names’, those who are successful, but what about the artist who does not have that success? How do they survive? Must one necessarily suffer poverty to create ‘good art’ as is often claimed? What is the reality, especially for the female visual artist?

Art education

75% of visual artists have a higher professional education (HBO) or university education (WO). In the period 2002-2022, 64% of the alumni were women. The majority of them are (ultimately) not working in the creative sector. Teachers at art schools are mostly women (52%), and leadership positions within art schools are also mostly held by women (62%).

Art history

Looking at art history, the visual arts have been a male-dominated domain. Women did create art but were denied access to art schools and were written out of art history. In the curriculum taught at art schools, women are heavily underrepresented.

Standard textbooks such as “History of Art” by H.W. Janson and “The Story of Art” by E.H. Gombrich did not include any female artists until recently. In the revised editions of 2014, more women are included, totaling 5%. This is still far from representative and inclusive.

Standard textbooks such as “History of Art” by H.W. Janson and “The Story of Art” by E.H. Gombrich did not include any female artists until recently. In the revised editions of 2014, more women are included, totaling 5%. This is still far from representative and inclusive.

Working hours

In the period 2017-2022, there were an average of 15,000 visual artists working, of which 54% were women. The average age was: 14% younger than 35 years, 39% between 35-55 years, and 47% older than 55 years. The majority (82%) of visual artists have one job in which they work approximately 28 hours per week. Those who have a second job work approximately 11 extra hours per week. Most visual artists work as self-employed individuals (94%) in the first job, and in the second job, this is 40%. Female visual artists (20%) more often have a second job (1 in 5 women). The research shows that women (and men) with young children tend to put their profession as visual artists on a ‘low flame’ during the ‘tropical years’ and seek financial security in a second job (as employees).

Personal and primary income

The research distinguishes between personal income and primary income.

- Personal income is the total gross annual income from labor and self-employment, including benefits from income insurance (unemployment benefits, sickness benefits, disability benefits, pension) and social provisions (social assistance, etc.).

- Personal primary income is only the gross annual income from labor and self-employment, excluding benefits from income insurance and social provisions. Personal income thus shows the total income someone has, while personal primary income provides insight into only the income someone has from labor and self-employment.

Looking at the total personal income of visual artists (both men and women), this averages around the social minimum, with most earning even below the social minimum (€20,200 – men / €16,900 – women).

Looking at the total personal income of visual artists (both men and women), this averages around the social minimum, with most earning even below the social minimum (€20,200 – men / €16,900 – women).

One-third of visual artists have a personal primary income of less than €10,000 per year, with only 5% earning more than €50,000 per year. In the age category of 55-64 years, the personal income for both men and women is notably low, less than €2,000 per year. 40% of visual artists generate no income from their own business.

Career trajectory

In the past 20 years, the number of female alumni from art schools has increased by 11%. The average age of alumni was 29 years. Male and female alumni start their careers in a proportionate ratio. 5 years after graduation, 29% of female visual artists work independently, while 43% are employed.

The research shows that female alumni with a degree as visual artists are more likely to receive benefits or have no income from the professional practice (visual artist). A majority of the alumni from visual arts programs are ultimately no longer working in the creative sector (60%).

Subsidies

The Boekman Foundation’s research distinguishes various funds aimed at stimulating the visual arts. These include national, provincial, and municipal subsidies, private and European funds, as well as 6 sectoral national cultural funds, including the Mondriaan Fund.

The Mondriaan Fund distinguishes between work contributions for young talent, proven talent, and project support. In the period 2017-2022, the applications of 77 emerging artists were granted. Of these, 40% were men, 57% were women, 2% were non-binary, and 1% were unknown. For applications for the next step in their careers, the ratio between men and women was roughly 60%/40%. It appears that women apply for less subsidy later in their careers. In project applications, there was equal treatment (50% women, 43% men, 7% non-binary). It was striking that women on average requested €1,400 less in subsidies than men.

At the Mondriaan Fund, in the period 2017-2022, the majority of applicants were men (731 men, 701 women, 40 non-binary), but there is now a trend emerging where women’s applications are more frequently granted (in 2022, this was 51.2%). However, it was found that men ultimately receive a higher share of subsidies. This is because men (59%) more often apply for subsidies in the basic scheme (€36,000 – €44,000) and women (57%) in the starter scheme (€18,000 – €22,000).

Art Prizes

In the Netherlands, there are 50 art prizes, with 4 prizes awarded annually and 3 prizes every 2 years. More information can be found on the Dutch Heights website. Winners of these 7 art prizes in the period 2017-2023 were 43% men, 54% women, and 3% a collective of artists. It was fairly evenly distributed. In 2 of the 7 prizes, women were even in the majority. Men less frequently win an art prize because they less frequently appear on a shortlist. Ultimately, women are more frequently awarded an art prize.

In the Netherlands, there are 50 art prizes, with 4 prizes awarded annually and 3 prizes every 2 years. More information can be found on the Dutch Heights website. Winners of these 7 art prizes in the period 2017-2023 were 43% men, 54% women, and 3% a collective of artists. It was fairly evenly distributed. In 2 of the 7 prizes, women were even in the majority. Men less frequently win an art prize because they less frequently appear on a shortlist. Ultimately, women are more frequently awarded an art prize.

Jury Panels for Art Prizes

Women (60%) are in the majority in the jury panels of various art prizes.

Representation of Female Visual Artists in Museums and Galleries

Museums

In 2019, the organization Mama Cash conducted research on the representation of female artists in museums. Here you can find the research The Position of ‘Women Artists in Four Art Disciplines in The Netherlands’

In 2019, the organization Mama Cash conducted research on the representation of female artists in museums. Here you can find the research The Position of ‘Women Artists in Four Art Disciplines in The Netherlands’

The research found that the number of female artists in collections on display was very low: 13%. In temporary exhibitions, female artists were represented at 30%.

The Volkskrant conducted research in December 2019 on the collections of 28 museums:: ‘How much attention do Dutch museums pay to female artists?’ It was found that 17% of the collections consisted of works by female artists, and that 30% of the works on display were by female artists.

Women Inc./ABN conducted research in 2022 titled ‘An Untold Story’. It was noted that it was clear there was gender inequality in museum representation. The extent of this inequality was not precisely determinable, but it was evident that there was currently no equal representation of men and women. One reason could be that funders hold a position of power and may impose certain conditions when providing subsidies.

Galleries

Little is known about the level of representation of female artists in Dutch galleries. Mama Cash mentions in their research a percentage of 42% female artists. Galleries in the Netherlands represent an average of 184 artists, with 32% recruited from graduation exhibitions. It appears that 64% of art buyers first visit a gallery.

Little is known about the level of representation of female artists in Dutch galleries. Mama Cash mentions in their research a percentage of 42% female artists. Galleries in the Netherlands represent an average of 184 artists, with 32% recruited from graduation exhibitions. It appears that 64% of art buyers first visit a gallery.

Gallery Owners

There are 91 galleries in the Netherlands. At 25 galleries (27%), leadership is in the hands of a woman. At 37 galleries, it is a man (41%). At 23 galleries (25%), there is both male and female leadership. Furthermore, there are 3 galleries (3%) with only a female owner and 3 galleries (3%) with only a male owner.

International

The Mondriaan Fund also supports Art Fair Int. They provide contributions to foreign galleries to promote work by living visual artists from the Netherlands (at fairs). In the period 2016-2022, the share of exhibited work at international fairs by male artists was 57.2%, by women 42.4%, and by non-binary individuals 0.4%.

Venice Biennale

In the first 100 years, 10% of the exhibited artworks were created by female artists. In the last 20 years, this grew to 30%, and in 2022, it was even 85%. Data from the Mondriaan Fund revealed that curators for the Dutch submissions in the period 1995-2024 were 68% male (14), 32% female (11), and 1 non-binary. The art shown was by 55% male artists, 42% female, and 3% non-binary artists.

Among the Dutch submissions for the Venice Biennale, male artists and curators were thus better represented than female artists and curators.

Reflections from the Field

- Male visual artists earn more than female visual artists, except for the age group 35-44 years. Women earn more in this group because they have a second job;

- Women are paid less for their art because they negotiate less effectively and ask for less for their art;

- Female alumni need more support in the business development of their artistic practice;

- Gaps in one’s curriculum vitae (such as due to pregnancy) are disadvantageous;

- Evaluation based on sales of artworks is not fair and not inclusive;

- Funds often require submitting recent work, but it should be possible for this to include work from the past 3-4 years;

- Women are more often negatively treated regarding pregnancy;

- Women are heavily underrepresented in the curriculum and canon of art;

- There is too much of a stereotype of female art, with women’s art being seen as soft;

- Themes that are difficult to digest are discouraged in art academies;

- Art by women is often associated with identity or femininity rather than the subject central to the artwork;

- For male white art, it is mainly viewed for the art itself and what it portrays;

- Museums often focus on one aspect (for example, on the representation of women or artists of color);

- There is increased awareness in museums about representation on boards, but these boards are still predominantly white;

- The gender of the director or curator often determines the choice of art/artist, and all variations should be considered;

- Female artists deal with sexist comments about their art, and they are often judged based on their appearance;

- Superstar effect, where a small group of successful female artists is primarily represented, is a market-driven phenomenon. Art is constantly drawn from a small pool of artists.

One might wonder why female visual artists still find themselves in a disadvantaged position. Fortunately, in 2024, the difference (in terms of income) with male visual artists is not as significant anymore. Historical bias is still a hurdle to overcome (see also my blog ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’). The art history of the visual arts was and is still a male-dominated sphere. Women did not have access to art education in the past (fortunately, they do now), and they were also written out of art history (this is gradually changing).

There is still a lack of opportunities for women to exhibit their work in museums/galleries. Power positions still predominantly belong to men. The research by the Boekman Foundation also shows that the representation of female artists strongly depends on the identity and background of the director or leader. The prevailing patriarchal system still perpetuates gender-specific stereotypes and unconscious biases about the work of female artists. This is unjust and unfortunate!

There is still a lack of opportunities for women to exhibit their work in museums/galleries. Power positions still predominantly belong to men. The research by the Boekman Foundation also shows that the representation of female artists strongly depends on the identity and background of the director or leader. The prevailing patriarchal system still perpetuates gender-specific stereotypes and unconscious biases about the work of female artists. This is unjust and unfortunate!

I wonder what has changed since 1989? Back then, the Guerrilla Girls’ slogan was

‘Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.’

Johanna