From curiosity to a struggle with …

Before I retired, about 5 years ago, I thought about what I would do when the time came. One of my ideas was to delve more into art history and especially that of (modern) African and African-American artists.

Over the years I had visited many exhibitions and bought quite a few catalogs and books on famous artists, but these were mostly European (white, male) artists. Actually, this was not at all surprising since the museums mainly exhibited their work.

Catching up

I started catching up at the Vrije Academie with the Art History Colloquium, supplemented by lectures on Modern and Hypermodern art but African and African-American art was hardly touched upon there either. So I thought about learning it through books, but to my surprise, I also saw almost no books on (modern) African and African-American art in museum stores and bookstores.

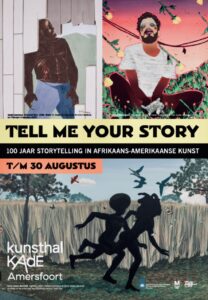

Tell Me Your Story

For me in 2020, the exhibition Tell Me Your Story at Kunsthal Kade in Amersfoort was a beginning. The exhibition started at the Harlem Renaissance and through it I was introduced to the core figures of African-American art and got leads to explore contemporary artists as well. The curator of the exhibition was Rob Perree, writer, art historian and in charge of the website Africanah, an Arena for Contemporary African, African-American and Caribbean Art.

Metropolis M

In Metropolis M, however, I read a (critical) review of ‘Tell Me Your Story’ written by Karima Boudou that got me thinking.

Here are two quotes:

Here are two quotes:

‘Tell Me Your Story’ is a very welcome and good starting point for a discussion on how Dutch museums can deal with such artistic practices and histories.

But I would not immediately call it a good example already. For that, the legitimacy of the chronological framework of 1920-2020 raises too many questions, in a Dutch context in which there is still insufficient understanding of African-American history and artistic movements.’

‘During my visit to ‘Tell Me Your Story’, the question constantly arises as to whether the exhibition has found an appropriate way to represent one hundred years of African-American art. The exhibition suggests that African-American art is a history in itself, which is a highly selective approach that reinforces an easily digestible image. An examination of the institutional mechanisms that generate recognition is necessary.

I am reminded in this regard of artist and philosopher Adrian Piper’s letter to the editor of The New York Times Magazine, in which she mentions in response to Thomas Chatterton Williams’ description of her work that it was not her decision ‘to stop showing with artists of color, but rather to stop showing in racially segregated exhibitions, i.e. those comprising only African American artists.’

Well …

And then I am an average art lover who wants to expand my horizons and begin to understand the motivations and backgrounds of African and African-American artists. I try to get a handle on the developments, the how and why and then it turns out that it is all much more complex. As a result, it has now also become a struggle and challenge for me in which I would like to be guided by experts.

And then I am an average art lover who wants to expand my horizons and begin to understand the motivations and backgrounds of African and African-American artists. I try to get a handle on the developments, the how and why and then it turns out that it is all much more complex. As a result, it has now also become a struggle and challenge for me in which I would like to be guided by experts.

The experts

But I see that I am not the only one struggling but also that museums are preoccupied with the question of how to give shape to the process of change and to the ICOM (International Council of Museums) rewritten definition of what a museum should be namely: ‘a democratizing, inclusive and multi-voiced space for critical dialogue about the past and the future’. Funny really that something like this is happening so late in time. I actually expect art historians, with their academic background, to have had a ‘broader and more thoughtful view’ of developments in the (art) world.

White balls on walls

Meanwhile, the documentary ‘White balls on walls’ by Sarah Vos was released, which followed the renewal process at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Dr. Charl Landvreugd, Head of Research & Curatorial Practice at the museum said, among other things, ‘as soon as it’s about black or brown people in art, it’s about ethnicity. Works from former colonies are often referred to as artifacts or objects for use, while works from Europe are called art, products of a genius mind.’

Arrogant

I think it is very bad that this has been the case until now. What arrogance and complacency has prevailed in the art and museum world and how fooled I feel! Rein Wolfs, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam talks (in the interview at De Balie), about ‘the white canon that needs to be torn down’, in other words the whole system needs to be shaken up! Another of his statements in the documentary is, ‘When all members of a group are part of the same system, they often unconsciously perpetuate the workings of that system. Some call that systematic racism. I can relate to that.’

I think it is very bad that this has been the case until now. What arrogance and complacency has prevailed in the art and museum world and how fooled I feel! Rein Wolfs, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam talks (in the interview at De Balie), about ‘the white canon that needs to be torn down’, in other words the whole system needs to be shaken up! Another of his statements in the documentary is, ‘When all members of a group are part of the same system, they often unconsciously perpetuate the workings of that system. Some call that systematic racism. I can relate to that.’

Metropolis M also wrote about ‘White balls on walls’

Shift

With me, a shift took place. I wasn’t just looking more at African-African American artists but I wondered what it was and is like in the Netherlands for artists from Caribbean and Surinamese backgrounds and who are they?

With me, a shift took place. I wasn’t just looking more at African-African American artists but I wondered what it was and is like in the Netherlands for artists from Caribbean and Surinamese backgrounds and who are they?

I discovered …

Iris Kensmil at Art Institute Melly in Rotterdam

Natasja Kensmil through the program Close up ‘You want it darker’ and at the Dordrecht museum where they acquired from her the ‘wedding portrait of Johan de Wit and Wendela Bicker’ (2020).

Marcel Pinas via ‘De Grote Suriname Tentoonstelling’ at the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam

Patricia Kaersenhout at the ‘Visions of Possibilities’ exhibition at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht

Carlos Blaaker at the Stedelijk Museum in Schiedam The latter museum purchased 26 works by 6 artists rooted in Curaçao.

Nelson Carrilho by the documentary ‘Ik ben een zwarte beeldhouwer’.

Sasha Dees ‘Entangled Species’, Conversations on Contemporary Art in the Caribbean, the book in which she takes us with her on a personal journey showcasing the depth and variety of artists and art communities of the Caribbean.

Serious change or a fashion trend?

Is it now suddenly ‘hot’ for museums and galleries to pay more attention to non-Western art? Fortunately, there is now a thorough study by Dr. Charl Landvreugd. He received his doctorate on the topic ‘Imagining, Tracing, Experiencing, Inhabiting, Projecting: Locating Afro artists as culturally native to the Dutch art world’ from the Royal College of Art in London in 2019.

Still, I am not entirely comfortable with it. After all, I read the interview with Rutger Pontzen, who was art editor at de Volkskrant for more than 20 years. In his farewell interview of April 19, 2024, he indicates, among other things, that ‘the inhabitants of the art world, especially those on the museum isle, do not necessarily have the best-equipped antennae for what is going on around them, let alone a forward-looking eye, even if they think they do.’ He indicates that it has ‘always amazed him: that high moral self-esteem. That position of exception. And at the same time the degree of conformism. That, once it becomes bon ton to pay more attention to women and non-Western artists, everyone backs each other up. It is difficult to be truly visionary and distinctive.’

Still, I am not entirely comfortable with it. After all, I read the interview with Rutger Pontzen, who was art editor at de Volkskrant for more than 20 years. In his farewell interview of April 19, 2024, he indicates, among other things, that ‘the inhabitants of the art world, especially those on the museum isle, do not necessarily have the best-equipped antennae for what is going on around them, let alone a forward-looking eye, even if they think they do.’ He indicates that it has ‘always amazed him: that high moral self-esteem. That position of exception. And at the same time the degree of conformism. That, once it becomes bon ton to pay more attention to women and non-Western artists, everyone backs each other up. It is difficult to be truly visionary and distinctive.’

In the same interview, he said:

‘Surely the best thing art can cause is that it challenges your own taste. That your assumptions are challenged of what is beautiful or ugly, good and bad, intriguing or soporific. Art may appeal to your empathy, ask you to empathize with what others make. Even if you don’t have much affinity for it.’

I can fully agree with the latter. It is clear from my story above that through art I have been incredibly challenged to ask myself all sorts of questions such as about to what extent I have been influenced throughout my life by the choices of others (read: art historians, museum directors, gallery owners and journalists). I realize now how limiting that has been and that a shift is taking place now. That I can still witness it makes me happy.

Johanna